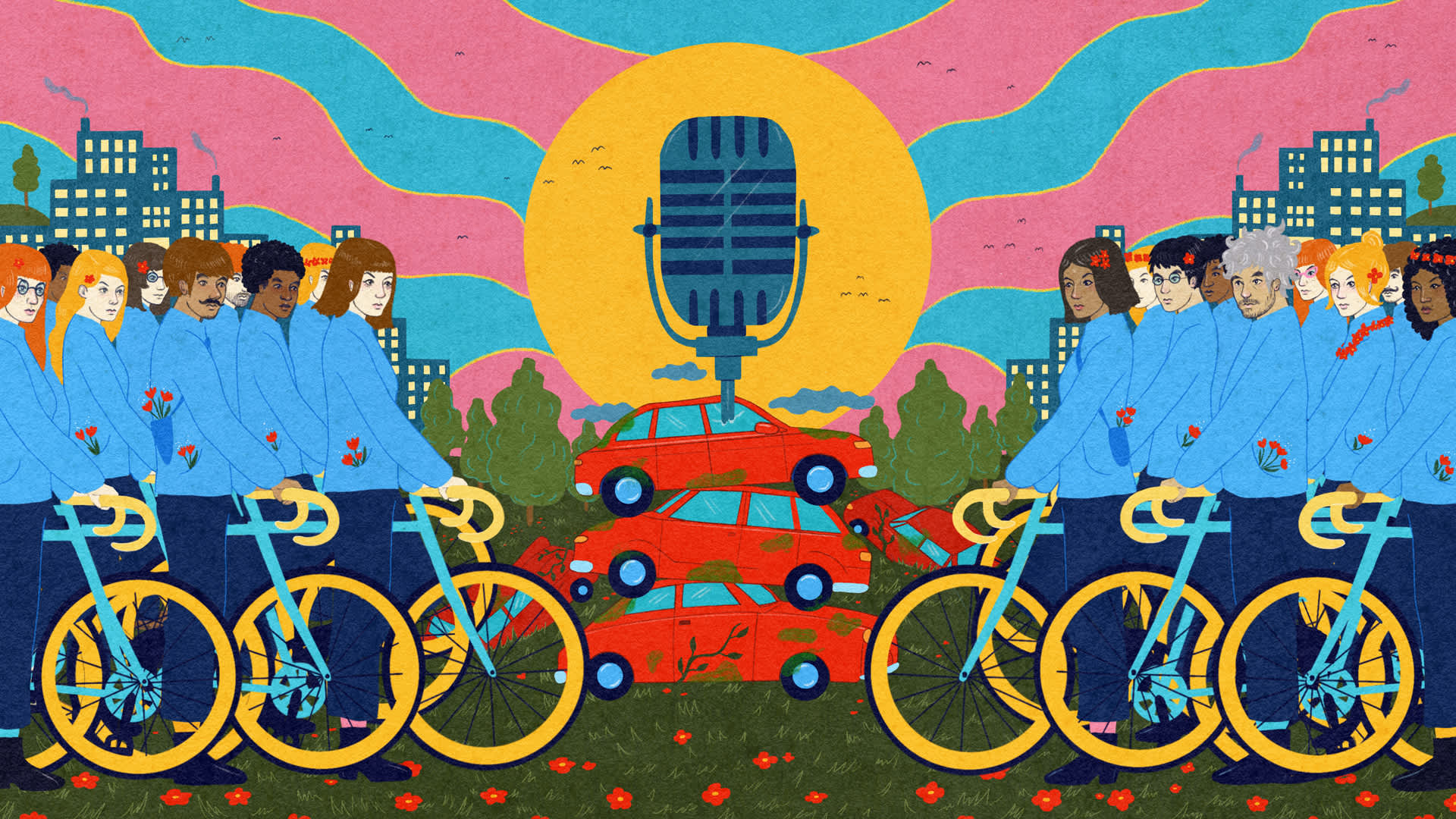

Every few weeks or so, on an industrial block in Gowanus, Brooklyn, that is slowly turning over to boutique hotels, craft distilleries, and axe-throwing establishments, the three hosts of The War on Cars gather to record a new episode. For the past four years, the podcast has been casting a gimlet-eyed look, by turns indignant and humorous, on the pernicious ubiquity of the automobile in American society.

The podcast operates under the general principle that the car, as a device and as a way of life, is at odds with healthy cities. Cars, the argument goes, are dangerous, polluting, loud, expensive, and frequently unnecessary — and yet most of our cities are designed, intentionally or not, to encourage as much automobile use as possible. Highways are widened while public transit is underfunded. Zoning hinders walkability by keeping residential and commercial areas separated. Even idle, cars cause trouble: Parking them — and they do sit parked for most of their life — gobbles up precious urban space.

And yet, the show is passionate without being doctrinaire, mining the wonky world of neckdowns and parking minimums for not just insight but laughs — sometimes of the awkward variety. Last year, its hosts infiltrated the New York International Auto Show, which resulted in a tetchy back and forth with a game-but-perplexed Dodge spokesman who noted that the key statement of his brand’s muscle cars is: “I’m here to rule the road.” Other episodes have ranged from Elon Musk takedowns to an annual analysis of all the car ads during the Super Bowl to a profile of “Mr. Barricade,” the transportation engineer who has become an unlikely TikTok influencer. (From time to time, they’ve also hosted guests who are less than enthusiastic about rideshares, and Lyft in particular.)

Funded largely by Patreon contributions and some bike-company sponsors, The War on Cars clocks somewhere around 30,000 listeners an episode — not massive, but far from casual. It is not uncommon for people to show up at community board meetings clad in War on Cars merchandise. One ardent listener tattooed a War on Cars slogan onto her thigh. Fans include columnist Dan Savage and entrepreneur Anil Dash, both of whom ended up on the show. Even Ray Magliozzi, one half of the famous Car Talk team — a figurehead of normie American car culture if there was one — has made an appearance.

One quiet winter afternoon, the three hosts gathered in the studio where they have been recording their episodes since 2018. It’s located — “rather appropriately,” says host Doug Gordon — next to an auto repair joint, just across the street from a brewery that serves as the podcast’s unofficial greenroom. The idea had been simmering for a few years before they launched, says Gordon, a television producer and longtime “livable streets” activist, as the movement is often dubbed. (Among other things, Gordon occasionally installed guerrilla traffic infrastructure — like driver-slowing traffic cones — throughout New York.) He’d been talking it over with Aaron Naparstek, a longtime journalist, transportation provocateur, and founder of the livable-streets standard-bearer Streetsblog.org. (Naparstek was also the author of Honku: The Zen Antidote to Road Rage, a collection of poems in response to the chronic line of traffic stewing and spewing outside his apartment in otherwise quiet brownstone Brooklyn.)

Working with Curtis Fox, a veteran radio producer, in 2016, they eventually created a pilot episode of a podcast they dubbed “Streetspod.” They invited Sarah Goodyear, a journalist and livable streets ally, to join them. (“A podcast with two white dudes talking — the world doesn’t need another one of those,” jokes Gordon.) They sent it around to some friends for feedback, but the idea basically languished. Then, in 2018, Gordon, having observed the huge upsurge in political podcasts after the 2016 election, finally decided the time was nigh. “I said, OK, I’m seeing all these different subjects get their own marquee podcasts,” he says. “I thought that we could do something a little different, something that treats cars, yes, as a policy problem but also as a cultural issue.”

At the time, Naparstek says, most livable-cities advocates were largely focused on adapting to cars — using nudges like narrowing streets to reduce their impact — rather than focusing on the two-ton elephants themselves. “If cars keep getting bigger, more powerful, more distracting, you’re imposing this cost on the public instead of asking the automakers to change what they’re doing.” Rather than taking defensive measures, they wanted to focus on the weapons themselves: cars.

Once they committed, the ideas came in droves — seemingly every aspect of contemporary life intersected with cars in some way. “That’s when I thought,” Gordon says, “we really have something.” What they didn’t have was a name. “Streetspod” had been an unsexy placeholder, and they kicked around various options — like “The Spokespeople” — that always seemed to involve cutesy bike-related puns. One day, Goodyear threw out a tagline: “The podcast of the War on Cars.”

The phrase “war on cars,” which barely seemed to exist during the more than 100 years the car slowly conquered the U.S. landscape, began to gain traction in the past few decades. Most often it’s used as a pejorative, like “The War on Christmas,” a way to protest any action that might reallocate urban space away from automobiles. “Whenever you are doing advocacy,” says Naparstek, “and you go out to fight for a new bike lane, or a new bus lane, or even just something meager, like a bike rack in front of your kid’s school, somebody will inevitably pop up and say, ‘These people are waging a war on cars.’ ” Rather than shrink from that term, he says, the team decided to “just be The War on Cars. They’re accusing us of that anyway.”

It wasn’t only ironic, either. “I really feel like we do need a war on cars,” Naparstek says. “They are doing violence to us in cities, in communities, on the planet. It’s a name that invites people into this struggle.”

Yet it could also turn people off, invoking a heady cloud of New York smugness. While Gordon admits to an“elitist Brooklyn attitude of ‘thank God we don’t have to drive everywhere,’ ” what makes the podcast refreshing is that it tries to meet people where they live — which in America typically involves a car. Naparstek, for example, did a multipart segment on a flourishing underground muscle car scene in New York City. “I really hate those guys,” he says. “They drive up Fourth Avenue and make tons of noise, and my dog has become more neurotic.” But rather than simply denounce the trend, he goes for a ride with one of its participants that turns into a curiously poignant voyage of understanding, and he eventually finds himself at a big-box parking lot after midnight watching hemi-engine-equipped drivers do donuts — until the police show up.

“I don’t think the podcast would have found the audience in the way it did,” says Gordon, “if we just came out, guns blazing — if you drive, you’re a terrible person. If I can get my mother-in-law, who lives in suburban Chicago and drives a convertible, to listen to it, I consider that a victory.” As the name suggests, its war is on cars, not drivers. “Part of what we’re doing,” says Gordon, “is we’re saying that the entire system of driving sucks, and it sucks most for the people who are dependent on it.” Goodyear points to an episode about a driver who, several decades ago, struck and killed a pedestrian. (“When you kill someone with a gun, you deal with the criminal justice system,” she said in the episode. “When you kill someone with a car, you deal with an insurance company.”) She says her conversation was “one of the most intense interviews I’ve ever done.” Goodyear says a sense of compassion is key. “I didn’t talk to her like, ‘My God, how could you have possibly killed someone with a car?’ I know how you could kill somebody with a car.”

Central to the podcast’s mission, says Goodyear, is getting people to recognize their own “car blindness.” She gives the example of residents complaining about a new bike-share station in a landmark neighborhood while ignoring the $75,000 Range Rover sitting right next to it. They’re trying to shine a light on a blight that is so familiar that we no longer see it.

With their centenary episode approaching, there’s no sign that they’re running out of gas, or taking their eye off the road ahead. They still have day jobs, but their Patreon support has been steadily increasing — as has their cultural cachet. (A War on Cars sticker, Gordon proudly notes, recently showed up in a New York Times photo.) They have no illusion of making any sizable dent in motordom, but, as in their sold-out live events, they have the feeling, Naparstek says, that “we are successfully giving voice, creating community, and generating some kind of movement-building effect.”

The content provided in this article is for informational purposes only. Unless otherwise stated, Lyft is not affiliated with any businesses or organizations mentioned in the article.